Updated January 28, 2026

The Layoff Surge vs. the “Booming” Job Market: What the Data Really Shows

Over the past year, a glaring disconnect has emerged in the American labor market. On one hand, government officials and many headline economic indicators continue to describe the job market as strong—sometimes even “booming.” On the other hand, a steady drumbeat of corporate restructuring and mass workforce reductions has pushed layoffs back into the center of the national conversation. For workers, investors, and local communities, the lived experience often looks less like a boom and more like a slowdown: hiring freezes, rescinded offers, “role eliminations,” and reorgs that quietly remove entire layers of staff.

The contradiction is not simply a matter of political spin versus pessimistic media coverage. It stems from a real tension in how labor-market health is measured. The unemployment rate can remain relatively low while large employers cut thousands of jobs, especially if displaced workers quickly find new work, move into contract roles, or exit the labor force entirely. And official statistics can lag, smoothing out shocks that are obvious to those inside industries undergoing rapid change. When you zoom in—sector by sector, job family by job family—the picture becomes more complex than the “booming” label suggests.

What Layoffs.fyi Shows: A Clear Surge in Workforce Reductions

One of the most widely referenced independent datasets tracking the scale of recent job cuts is Layoffs.fyi, which aggregates publicly reported layoffs, company announcements, and corroborated reports, particularly in technology and tech-adjacent industries. While it is not an official government dataset, it has become an important real-time barometer because it updates quickly and captures layoffs in the very sectors that helped power earlier growth narratives.

The topline trend from Layoffs.fyi is hard to ignore: layoffs have remained elevated well beyond the “post-pandemic normalization” story. Even as some parts of the economy continued to add jobs, the tech sector—along with venture-backed firms and a widening circle of white-collar employers—kept cutting. The site’s year-by-year counts show that this isn’t a brief blip. It’s a sustained labor rebalancing that has dragged on long enough to change bargaining power in many professional roles.

That matters because tech layoffs do not stay neatly within tech. Technology firms sit at the center of modern business operations (cloud, e-commerce, advertising, logistics software, cybersecurity, enterprise tools). When those firms retrench, the impact spills into contractors, staffing agencies, marketing ecosystems, local real estate markets, and small businesses that depend on high-income consumer spending.

High-Profile Cuts Signal Something Deeper Than “Right-Sizing”

One reason layoffs feel inconsistent with “booming” claims is the identity of the companies cutting jobs. This is not limited to marginal firms running out of cash. Many layoffs are coming from large, well-capitalized organizations (Like UPS)—often framed as strategic “efficiency” moves rather than emergency measures. But scale matters: when a major employer cuts thousands of workers, the aggregate pain is real regardless of how the press release is worded.

Recent announcements underscore this pattern. Large rounds of corporate layoffs have been attributed to a mix of cost control, organizational flattening, and shifting investment priorities. Across the market, you see similar themes: consolidate teams, reduce duplicated functions after acquisitions, and prioritize fewer “must-win” projects. For employees, this frequently translates into fewer internal transfer options and more competition for each open role.

Importantly, the layoff wave has expanded beyond the classic “big tech” bucket. Logistics, retail, telecom, and consumer brands have also announced significant job cuts. Some of these reductions reflect slowing demand after unusually strong pandemic-era volumes. Others reflect margin pressure, higher financing costs, and supply-chain realignment. And in some cases, companies are cutting simply because they can: they have learned that markets reward cost reductions and that productivity can rise even as headcount falls.

Why “Booming” Can Be Technically True—and Still Misleading

The phrase “booming job market” usually refers to a few headline measures: a low unemployment rate, steady payroll growth, and relatively contained weekly jobless claims. Those indicators can remain healthy even while layoffs rise in specific sectors. That’s partly because the U.S. economy is enormous and diverse; growth in healthcare or hospitality can offset cuts in software or corporate services.

But that statistical reality can obscure where the stress is concentrated. If layoffs disproportionately hit high-wage, white-collar roles, the national unemployment rate may not spike immediately, but the consequences can still be severe: household budgets tighten, discretionary spending slows, and career trajectories get disrupted. In addition, a labor market can be “tight” in some occupations while being brutally competitive in others.

Another reason the “booming” narrative can coexist with layoff headlines is churn. A labor market can show net job growth even if many people are losing jobs—so long as hiring elsewhere outpaces separations. That may sound reassuring, but it fails to capture a key question: are the new jobs comparable in pay, stability, and career progression to the jobs being eliminated? If a mid-career product manager loses a role and later takes a lower-paid contract job, the headline statistics may count that as “employed,” while the worker’s financial reality deteriorates.

Structural Forces Driving Layoffs

1) Higher Cost of Capital and a Shift in Corporate Priorities

As interest rates rose from the ultra-low environment of the late 2010s and early 2020s, the incentives that fueled aggressive hiring changed. When money is cheap, companies can justify growth-at-all-costs strategies and large headcount expansions. When borrowing costs rise and investors demand profitability, companies cut “nice-to-have” projects and reduce operating expenses—often by eliminating roles.

This shift is especially pronounced in venture-backed and high-growth companies, where future earnings are discounted more heavily in higher-rate environments. Even profitable firms have adopted the same discipline, aiming to show shareholders “operational rigor.” In plain language: companies are choosing margin and efficiency over expansion.

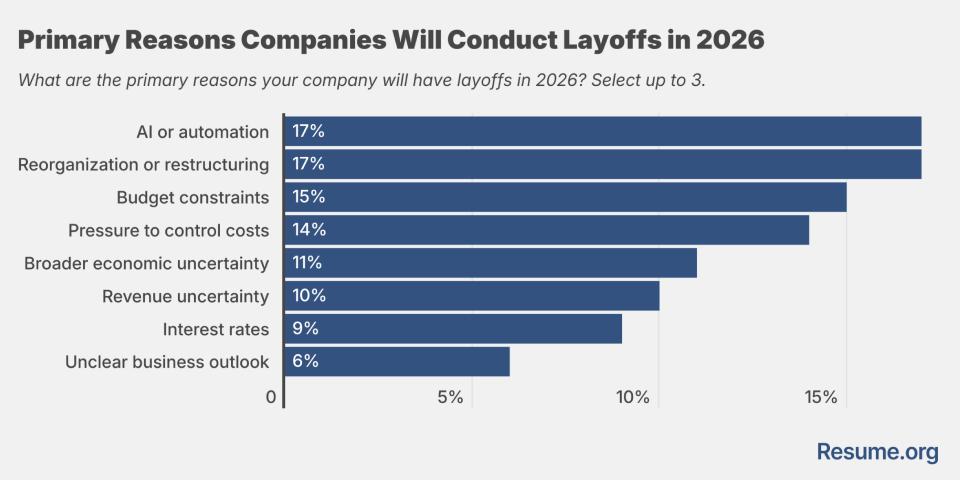

2) AI, Automation, and the Recomposition of White-Collar Work

Artificial intelligence is frequently cited in layoff announcements and internal memos. The effect is not always direct job replacement (a bot taking a human’s exact role), but rather a reorganization of workflows that reduces the number of people required. When one employee can produce more output with AI tools—whether in code generation, customer support triage, marketing content, analytics, or internal operations— companies often respond by shrinking teams and raising performance expectations for those who remain.

The result is a “productivity shock” that can look like a boom in output but a bust in headcount for certain functions. Importantly, this can happen even without an overall recession. A company can be healthy, demand can be stable, and layoffs can still occur because management believes the same work can be done with fewer employees.

3) Post-Pandemic Demand Normalization and Supply-Chain Realignment

Pandemic-era behavior produced unusual spikes in e-commerce, home goods, and certain logistics services. As consumer patterns normalized, some firms found themselves overbuilt. Companies that scaled rapidly to meet peak demand now face the inverse problem: excess capacity. Layoffs become a tool to align costs with more moderate growth expectations.

At the same time, broader supply-chain strategies—reshoring, “friend-shoring,” inventory adjustments, and geopolitical risk management— have introduced new uncertainties. Businesses navigating shifting input costs and trade dynamics often respond by slowing hiring or cutting roles in non-core areas.

The Human Impact: Why Layoff Waves Matter Even When Headline Metrics Look Fine

Macro indicators can be cold comfort to households dealing with job loss. Layoffs are not merely a temporary inconvenience; for many workers, they trigger cascading consequences: depleted savings, delayed medical care, postponed home purchases, and long-term earnings setbacks. Professional layoffs often come with additional friction—skills mismatch, regional concentration (e.g., tech hubs), and a hiring market that may be far less forgiving than the one that existed a few years ago.

The psychological toll is also significant. Repeated layoff cycles create a culture of insecurity, even among those still employed. Workers become less likely to take risks, change jobs, or negotiate for raises. That dampens wage growth and can feed back into consumer spending, especially in metro areas where layoffs concentrate among higher earners.

So Is the Job Market Booming—or Not?

The most accurate answer is that the U.S. job market is uneven. It may be strong in aggregate while deteriorating sharply in specific sectors, regions, and job categories. That’s precisely why simplistic “booming” claims can ring hollow: they describe an average, not an experience. For a nurse, a construction worker, or a hospitality employee in a high-demand market, conditions may indeed feel strong. For a software engineer, recruiter, product marketer, or corporate operations professional—especially in tech-saturated regions—the market can feel like a downturn.

Layoffs.fyi captures the intensity and persistence of this shift, especially within the tech ecosystem that once symbolized endless growth. Its data does not necessarily mean the entire economy is collapsing, but it does undermine the idea that a strong national labor market automatically translates into broad-based employment security.

What to Watch Next

Several indicators can clarify whether layoffs remain a sector-specific correction or become a broader labor market problem:

- Hiring rates and job openings: If openings fall while layoffs rise, displaced workers will struggle longer to find comparable roles.

- Wage growth by occupation: Slowing wage growth in professional categories can signal a shift in bargaining power and labor demand.

- Duration of unemployment: Even with a low headline unemployment rate, longer job searches can indicate hidden weakness.

- Sector breadth of layoffs: If cuts spread from tech and corporate services into a wider range of industries, the risks increase.

Conclusion

The surge in layoffs, particularly as documented by Layoffs.fyi, complicates the government’s “booming job market” framing. The labor market can look strong through certain official lenses while still producing widespread insecurity, especially in industries undergoing structural change. The more honest story is not a binary boom-or-bust narrative, but a bifurcated economy: resilience in some sectors, retrenchment in others, and a growing role for automation and cost discipline that reshapes what “good” labor-market health really means.

For policymakers, the challenge is to recognize that headline numbers can mask real damage in specific communities and professions—and that repeated layoff cycles can erode long-term confidence even without a formal recession. For workers, the lesson is equally stark: the market may be “booming” on paper, but the risk of displacement has become a defining feature of the modern economy.

If you need employment litigation, please call Setyan Law at (213)-618-3655. Free consultation.